Estimated read time: 15 minutes

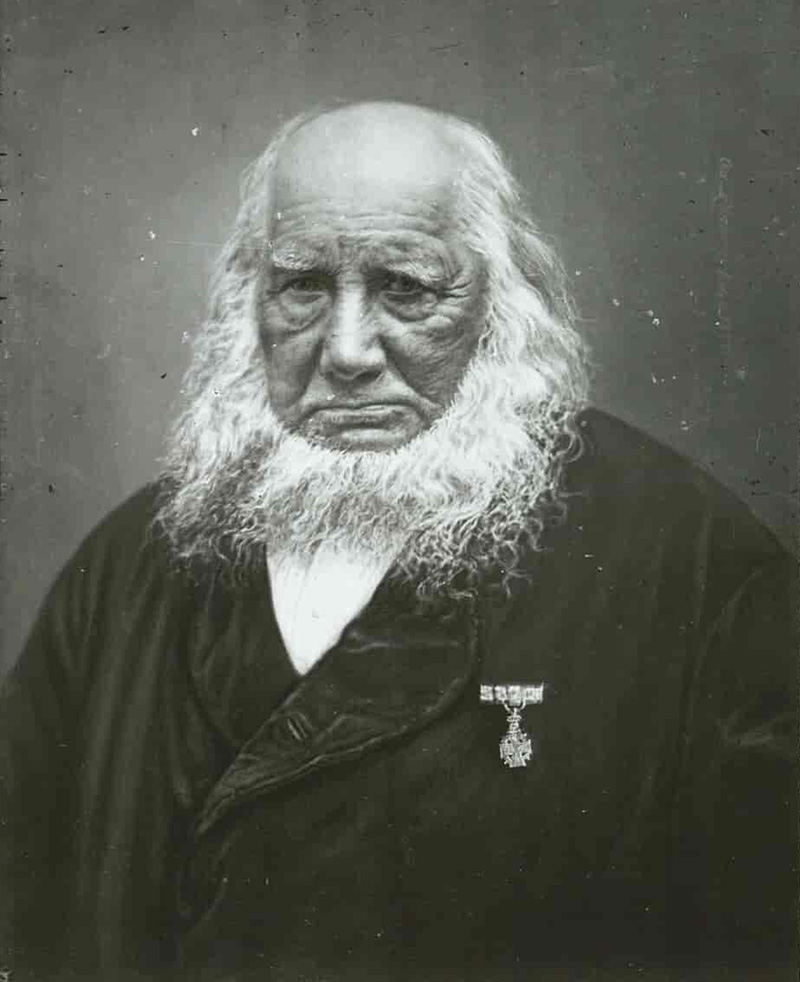

Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (1783–1872) was a Danish pastor, theologian, poet, historian, and political thinker whose revolutionary ideas helped lay the foundation for modern Danish society. Known as the father of the folk high school movement, Grundtvig’s influence extended across education, religion, and politics, transforming Denmark during a time of profound social and economic change.

Born on September 8, 1783, in the small village of Udby on Zealand, Grundtvig grew up in a Lutheran household. His father was a strict, orthodox pastor, while his mother brought a more open-minded and intellectual perspective. These contrasting influences would later shape Grundtvig’s philosophy, blending tradition with a progressive outlook.

In his youth, Denmark was a nation in transition. The old feudal system was beginning to crumble, and Enlightenment ideas of reason, progress, and equality were challenging rigid social norms. Grundtvig’s education at the University of Copenhagen exposed him to these shifting currents. After graduating in theology, he worked as a tutor and later as a pastor, but he quickly grew dissatisfied with what he saw as a lifeless and rigid approach in both education and religion. He dreamed of something different—a way to connect more deeply with the lives and aspirations of ordinary people.

The early 19th century was a turbulent period in Danish history. The Napoleonic Wars had left the country economically devastated, culminating in the loss of Norway in 1814. The traditional feudal order was giving way to new social and economic structures, and Denmark faced an urgent need for national renewal. Grundtvig recognized the potential of education and cultural revival as tools for rebuilding the nation.

His experiences as a pastor led him to critique both the educational and religious institutions of his time. He believed that the state-controlled educational system, rooted in rote learning and authoritarianism, stifled creativity and individuality. Similarly, the church’s focus on doctrine alienated the common people from their faith. For Grundtvig, the answer lay in empowering the individual through education and reconnecting people with their cultural and spiritual heritage.

The Most Terrible Night. View of Kongens Nytorv in Copenhagen During the English Bombardment of Copenhagen at Night between 4 and 5 September 1807. Painting by C.A. Lorentzen.

As a theologian, Grundtvig sought to reform Christianity by emphasizing the living word and the communal aspects of faith. He famously criticized the Danish church in his essay Kirkens Gienmæle (1825), arguing that Christianity should be rooted in a living connection to tradition rather than rigid dogma. His focus on hymns, oral liturgy, and the Apostles’ Creed reflected his belief in a faith that could be experienced collectively and joyfully.

This emphasis on communal spirituality resonated with a growing sense of Danish nationalism. Grundtvig believed that a strong national identity was essential for Denmark’s survival and renewal. He saw Christianity and Norse mythology as complementary forces in shaping the Danish spirit, and his historical writings celebrated the Viking Age as a source of inspiration and pride.

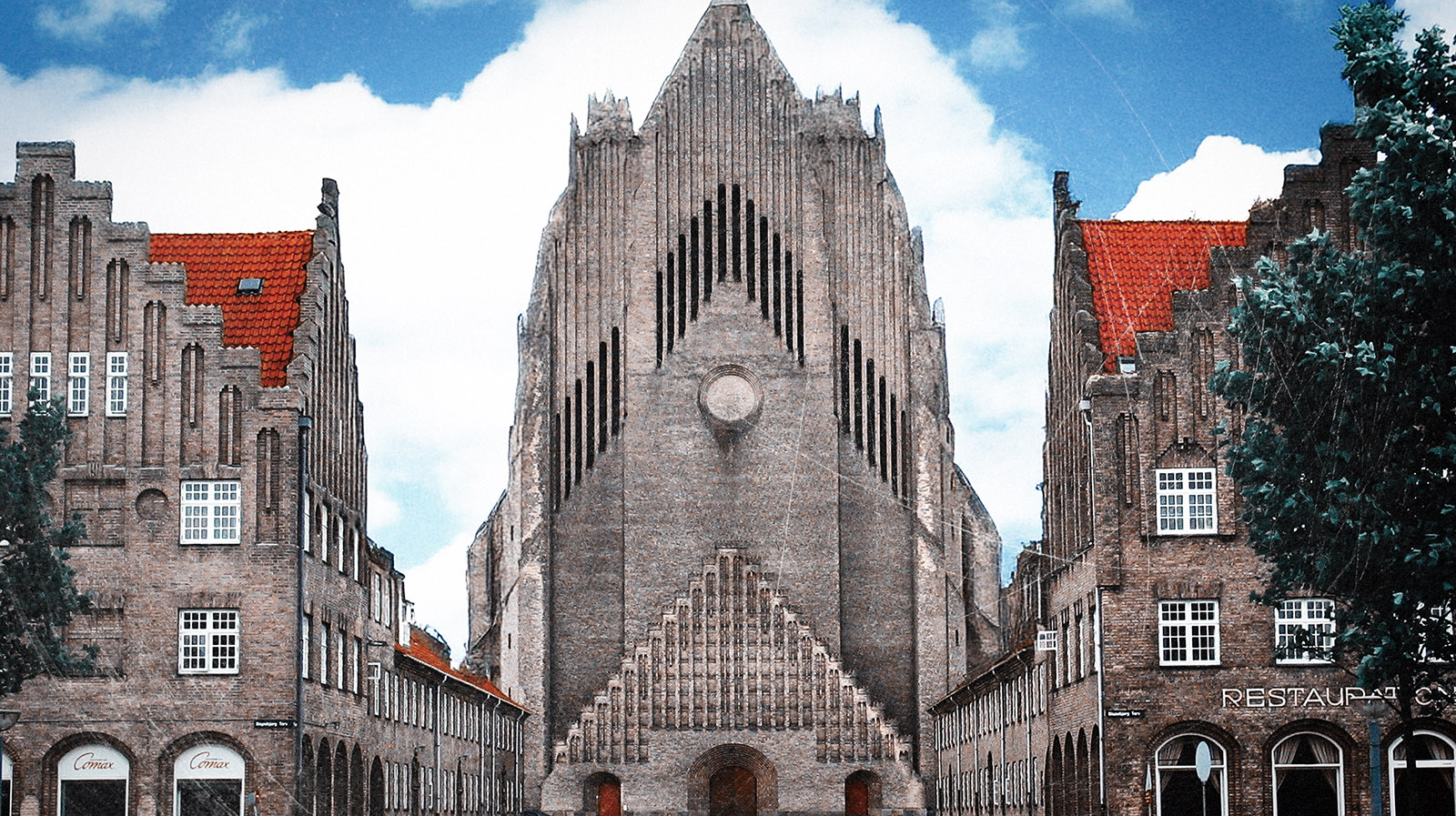

Grundtvig wrote more than 1,500 hymns, many of which remain staples in Danish worship. His most famous works include “God’s Word Is Our Great Heritage,” “Built on a Rock, the Church Doth Stand,” and the Christmas carol “The Happy Christmas Comes Once More.” The 2002 edition of Den Danske Salmebog (The Danish Hymn Book) includes 163 original hymns and 90 adaptations, highlighting his central role in shaping Danish hymnody. The picture above shows Grundtvig’s Church in Copenhagen, a landmark of Danish expressionist architecture built between 1921 and 1940.

Grundtvig’s most groundbreaking contribution was his idea of the folkehøjskole (folk high school), which he envisioned as a place where young adults, particularly from rural areas, could gather to learn, reflect, and develop as whole persons. Unlike traditional schools, folk high schools would focus on practical and cultural education rather than exams or formal qualifications.

Grundtvig believed education should foster enlightenment (“oplysning”)—a concept he interpreted as “life enlightenment,” where students would gain a deeper understanding of themselves, their community, and their role in society. History, poetry, and the oral tradition were central to this vision, as he saw them as vital tools for building identity and fostering a sense of belonging.

The first folk high school, established in Rødding in 1844, became a cornerstone of Denmark’s cultural and social renewal. Over time, the movement spread across Scandinavia and even inspired similar initiatives worldwide. Grundtvig’s ideas empowered rural communities, contributing to a sense of equality and democracy that reshaped Danish society.

Grundtvig’s influence extended to politics, where he championed democracy and social reform. He was a member of the Danish Constituent Assembly during the drafting of Denmark’s first democratic constitution in 1849, which established a constitutional monarchy. While not a radical democrat, Grundtvig believed in a society where all citizens—particularly the rural population — had a voice.

His democratic ideals were deeply intertwined with his educational philosophy. Grundtvig saw education as the foundation of an engaged and informed citizenry, capable of participating in public life. At the same time, he held conservative views on some issues, including a patriarchal view of family and society. This duality has made him a complex figure in the history of Danish democracy.

Despite his achievements, Grundtvig was not without his detractors. His romanticized view of rural life and the past was criticized for being impractical in an era of industrialization and urbanization. Some saw his ideas as nostalgic, failing to address the challenges of a rapidly modernizing society.

Additionally, while Grundtvig championed the idea of “the people,” his vision often excluded minorities and those outside the Nordic cultural sphere. Critics have pointed out that his nationalism, though culturally enriching, risked fostering exclusionary attitudes. Moreover, his perspectives on gender roles have been criticized for reinforcing traditional, patriarchal norms that limited women’s agency in both public and private spheres.

His theological reforms also sparked controversy. While many celebrated his focus on a living, communal faith, others found his theology overly vague and lacking in doctrinal clarity. His clashes with the Danish state church made him a polarizing figure in religious circles.

In 1867, during a Palm Sunday service at Vartov Church, 83-year-old N.F.S. Grundtvig experienced a dramatic mental breakdown. Believing himself to be the Archangel Gabriel, he stunned the packed congregation by confidently marching to the pulpit and delivering a six-hour sermon filled with erratic proclamations.

He invited unconfirmed individuals to take communion and addressed Queen Dowager Caroline Amalie, declaring Denmark’s sins forgiven with the prophetic words: “Now Jordan flows out into the Øresund”, linking biblical imagery to Copenhagen. He further claimed the queen, despite being over 70 years old, would give birth to Holger Danske, a mythical figure destined to save Denmark. Grundtvig also kissed women in attendance, believing this act would lead to virgin-born children.

Diagnosed with “excessive erotic excitement,” Grundtvig was taken to the countryside to recover. Despite the scandal, he later resumed his work, with his legacy and royal support intact.

Birth of N.F.S. Grundtvig in Udby, Zealand, Denmark. He is born into a Lutheran family, with a father who is a pastor and a mother with progressive intellectual leanings.

Grundtvig begins studying theology at the University of Copenhagen.

Denmark is drawn into the Napoleonic Wars. Copenhagen is bombarded by British forces, and the Danish fleet is destroyed.

Grundtvig works as a private tutor in Langeland, where he begins exploring history and Norse mythology, laying the groundwork for his later ideas.

Publishes Nordens Mythologi (Norse Mythology), a work that reflects his growing interest in blending cultural heritage with Christian values.

Denmark loses Norway (to Sweden) in the Treaty of Kiel, a major blow to the nation. Grundtvig sees this as a call for national renewal through education and culture.

Becomes pastor in Udby, his birthplace, and starts developing his ideas on a living and accessible Christianity.

Publishes Kirkens Gienmæle (The Church’s Reply), a theological critique of the Danish state church. This marks the beginning of his disputes with church authorities.

Grundtvig resigns from his pastoral duties due to conflicts with the state church but continues writing hymns and poetry.

Denmark begins agricultural reforms, gradually dismantling the feudal system. This period of change aligns with Grundtvig’s belief in empowering rural communities.

Publishes Sang-Værk til den Danske Kirke (Songbook for the Danish Church), containing many of his most famous hymns.

The first folk high school is founded in Rødding, inspired by Grundtvig’s educational philosophy. It aims to educate rural youth and strengthen their connection to Danish culture.

Revolutions sweep across Europe - and Denmark begins transitioning to a constitutional monarchy.

Grundtvig participates in drafting Denmark’s first democratic constitution, which establishes a constitutional monarchy and expands civil liberties.

Appointed pastor of the Vartov Church in Copenhagen, where he serves until his death.

Grundtvig celebrates his 50th anniversary as a writer, with widespread recognition of his influence on Danish education, religion and culture.

Denmark suffers another national defeat in the Second Schleswig War, further intensifying the need for cultural and national unity, a cause Grundtvig championed.

Grundtvig dies on September 2 in Copenhagen at the age of 88. He leaves behind a legacy of hymns, writings and educational reforms.

Grundtvig’s later years were marked by both personal and professional fulfillment. He continued to write, teach, and advocate for his ideas until his death in 1872. His impact on Danish society was widely recognized even in his lifetime, with his folk high school movement gaining traction and his hymns becoming beloved fixtures in Danish worship.

In his final years, Grundtvig reflected on the challenges and triumphs of his life, often emphasizing the importance of community, faith, and education in shaping a better future. He passed away at the age of 88, leaving behind a legacy that transcended his era. His work inspired generations to come, establishing Denmark as a model of lifelong learning and democratic engagement.

Today, Grundtvig’s philosophy of education and human enlightenment continues to inspire. His belief in the power of community, the value of culture, and the potential of the individual resonates in a world still grappling with questions of identity, inclusion, and democracy. When Grundtvig passed away in 1872, he left behind more than a legacy of ideas—he left a living tradition that continues to shape the world.

Sweden: Inspired by Grundtvig, the first Swedish folk high school was founded in 1868. The movement aligned with Sweden’s growing interest in adult education and grassroots mobilization, supporting agricultural communities and later expanding to urban workers. Folk high schools became a cornerstone of the labor movement, fostering leaders who would drive Sweden’s social reforms in the 20th century.

Norway: Folk high schools in Norway emerged in the 1860s and became tightly linked to the country’s national identity movement. They provided a space to celebrate Norwegian language, culture, and rural traditions, empowering citizens to engage in democracy during a time of increasing independence from Sweden (culminating in 1905).

Finland: Finnish folk high schools began in the late 19th century, adapting Grundtvig’s ideas to strengthen Finnish cultural identity during Russian rule. The schools helped foster a sense of unity and civic responsibility that contributed to Finland’s eventual independence in 1917.

Grundtvig was born on September 8, 1783, in Udby, a small village on Zealand, into a Lutheran family. His father was a conservative pastor deeply rooted in orthodox Christianity, while his mother’s more progressive and intellectual tendencies likely influenced Grundtvig’s later ideas. Denmark at the time was a society in transition, marked by the Enlightenment’s influence and upheavals from the Napoleonic Wars.

Questions to Reflect On:

The Napoleonic Wars had left Denmark economically devastated, and the loss of Norway in 1814 further weakened the nation. Amid this turmoil, Grundtvig saw education and cultural revival as essential tools for rebuilding a sense of national pride and identity. He critiqued rigid, state-controlled education for stifling creativity and individuality.

Questions to Reflect On:

Grundtvig’s folk high school concept emphasized practical and cultural education over formal qualifications. The first school in Rødding (1844) empowered rural communities and fostered a sense of belonging and enlightenment.

Questions to Reflect On:

Grundtvig sought to reform Christianity, moving away from rigid doctrines toward a faith rooted in the living word and communal worship. He believed that spirituality and cultural heritage were vital for building a strong national identity.

Questions to Reflect On:

Grundtvig contributed to the 1849 Danish Constitution, advocating for democracy while maintaining conservative views on societal roles. He saw education as the foundation for an informed citizenry capable of participating in public life.

Questions to Reflect On:

Critics have argued that Grundtvig romanticized rural life and overlooked the complexities of industrialization. His nationalism, while empowering, sometimes excluded minorities, raising questions about the inclusiveness of his vision.

Questions to Reflect On:

Grundtvig’s folk high school movement became a cornerstone of Danish democracy and inspired educational initiatives worldwide. His ideas remain relevant in discussions about lifelong learning and community-based education.

Questions to Reflect On:

The Grundtvig Lexicon

This lexicon explains key concepts and ideas from N.F.S. Grundtvig’s philosophy, focusing on education, community and lifelong learning.

Active Citizenship

A fundamental goal in Grundtvigian thought, emphasizing individuals’ active participation in democratic and societal life through education that fosters responsibility and engagement.

Assembly (Forsamling)

The gathering of people for open dialogue and shared learning, reflecting Grundtvig's belief in the folk high school as a space for communal and democratic education.

Bildung

A term closely tied to Grundtvig’s vision, often translated as "formation" or "cultural education," focusing on the holistic development of individuals in terms of personal, moral and social growth.

Bible as Poetry

Grundtvig viewed the Bible not only as a religious text but also as a source of poetic and existential wisdom, meant to inspire creativity and a deeper understanding of life.

Civic Education

Education aimed at cultivating democratic values, societal engagement, and the capacity to think critically and act responsibly in community life.

Christian Enlightenment

Grundtvig’s idea of integrating Christian spirituality with secular enlightenment, emphasizing human dignity, moral development and intellectual freedom.

Democracy

A cornerstone of Grundtvig’s educational philosophy, where democracy is understood as a lived practice, cultivated through participation, dialogue and mutual respect.

Dialogue

A central method of learning in Grundtvigian pedagogy, where open conversation fosters understanding, shared growth and the building of community.

Egalitarianism

The belief in the equal value and potential of all individuals, a principle embedded in Grundtvig’s vision for education and society.

Enlightenment of Life (Livsoplysning)

A core concept in Grundtvig’s philosophy, referring to an education that enriches and deepens life by connecting individuals to culture, history and shared human experience.

Folk High School (Folkehøjskole)

Grundtvig’s revolutionary educational institution, designed for adults to explore personal growth, cultural identity and democratic engagement without formal exams or rigid curricula.

Freedom

A vital concept for Grundtvig, encompassing both spiritual freedom and the freedom to think, express and live authentically in society.

Grundtvigianism

The cultural and educational movement inspired by Grundtvig’s ideas, emphasizing lifelong learning, community, and the interplay of faith, culture and democracy.

Historical Poetry

Grundtvig advocated teaching history as a living and inspiring narrative, blending factual knowledge with poetic imagination to connect learners with their cultural heritage.

Human Dignity

A foundational value in Grundtvig’s philosophy, affirming the inherent worth of every individual and the right to education that supports personal and societal growth.

Living Word

Grundtvig emphasized oral storytelling and dialogue, viewing the spoken word as vital for education, connection and personal enlightenment.

Lifelong Learning (Livslang Læring)

A core principle in Grundtvig’s educational philosophy, advocating for continuous personal development and learning throughout life, beyond formal schooling.

People's Church (Folkekirken)

Grundtvig’s vision of a church that is open, inclusive, and deeply connected to the lives and culture of the people it serves.

Singing Together

Group singing was central to Grundtvigian practice, fostering unity, joy and a sense of community through shared cultural expression.

Spirit of Freedom

An ideal guiding Grundtvig’s work, representing the human yearning for autonomy, creativity and self-realization within a supportive community.

Värdegrund (Values)

Though primarily a Swedish term, it reflects the influence of Grundtvigian ideals in Scandinavian education, focusing on shared values, community and democratic principles.

References