Estimated read time: 12 minutes

Folk high schools were part of a larger wave of educational reform sweeping across Europe. The 19th century saw the rise of movements advocating for universal access to education, fueled by revolutionary ideals of equality, democracy, and social justice. The revolutionary fervor of 1848 sparked calls for systems that empowered citizens to participate actively in shaping their societies. Across the continent, experiments in adult education, workers’ schools, and cooperative learning emerged, responding to the demands of industrialized societies and the aspirations of marginalized groups.

In Scandinavia, folk high schools represented a uniquely transformative approach. While other reforms focused on technical training or institutionalized education, these schools prioritized personal growth, cultural identity, and community resilience. Grounded in the philosophy of Danish theologian Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig, they championed holistic learning through dialogue and lived experiences. This blend of practical education and cultural preservation not only empowered rural populations but also inspired educational models around the world.

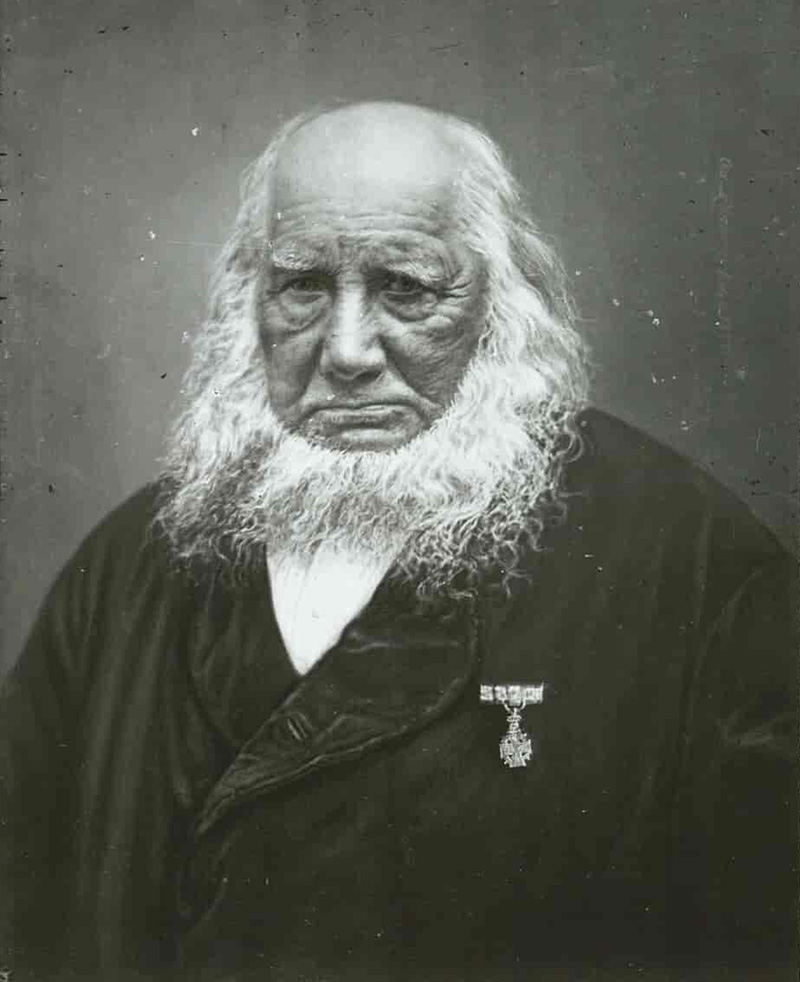

The revolutionary movements of 1848 swept across Europe, igniting calls for democracy, social justice, and national identity. These ideals deeply influenced the emergence of folk high schools, particularly in Scandinavia, where they underscored the role of education in fostering civic participation and cultural resilience. At the heart of this movement was the visionary Danish theologian Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig, who championed education as a tool for personal and societal transformation. His philosophy of the “living word” emphasized dialogue, cultural connection, and holistic development over rote memorization.

Denmark was the cradle of the folk high school movement, shaped by Grundtvig’s ideals. During an era of agrarian reforms and industrialization, these schools addressed the dislocation of rural communities and the growing economic divide between urban and rural areas. The first folk high school, Rødding Højskole, was established in 1844 in Schleswig. It aimed to educate and inspire rural youth, helping them understand their cultural heritage while preparing them for the challenges of a rapidly modernizing world.

Events like the Schleswig Wars (1848–1851 and 1864) highlighted the importance of cultural preservation, while the Constitutional Reform of 1849 marked Denmark’s democratic awakening. Folk high schools played pivotal roles in Denmark’s labor and cooperative movements, equipping workers with civic education and negotiation skills, empowering them to advocate for better conditions and unionization.

In Sweden, the folk high school movement emerged in response to the social and economic challenges of the 19th century, including the massive emigration of over 1.4 million Swedes to the United States between 1860 and 1920. These schools sought to improve economic prospects for those who stayed while preserving cultural ties. The first Swedish folk high schools were founded in 1868, inspired by the Danish model. They focused on providing practical and civic education to rural populations, fostering resilience, and strengthening national identity.

They became hubs for the labor and temperance movements, addressing pressing social issues through grassroots campaigns and educational programs. Notable figures like Per Albin Hansson, Sweden’s Prime Minister from 1932 to 1946 and the architect of the Swedish welfare state, found inspiration at institutions like Brunnsvik Folk High School (where his older brother worked as the director of trade union education programs). By hosting lectures and campaigns for social reform, Sweden’s folk high schools catalyzed the nation’s transition to universal suffrage and broader social equity.

Norway’s folk high schools emerged during a time of rural poverty and national transformation. While the movement was formally inspired by the Danish folk high school model, it also resonated with the earlier legacy of Hans Nielsen Hauge. Hauge’s emphasis on literacy, self-reliance, and community cooperation had left a lasting impact on rural Norwegian society, fostering values that aligned with the goals of the folk high school movement.

The first Norwegian folk high school, Sagatun Folk High School, was established in 1864 in Hamar by Herman Anker and Olaus Arvesen. It combined cultural education with practical skills, aiming to empower rural citizens and foster a sense of civic engagement. After Norway dissolved its union with Sweden in 1905, folk high schools became vital in fostering national identity. They promoted cooperative farming and rural electrification, enabling small-scale farmers and fishers to modernize their livelihoods. By linking education with practical solutions, these institutions bolstered Norway’s democratic progress and societal resilience.

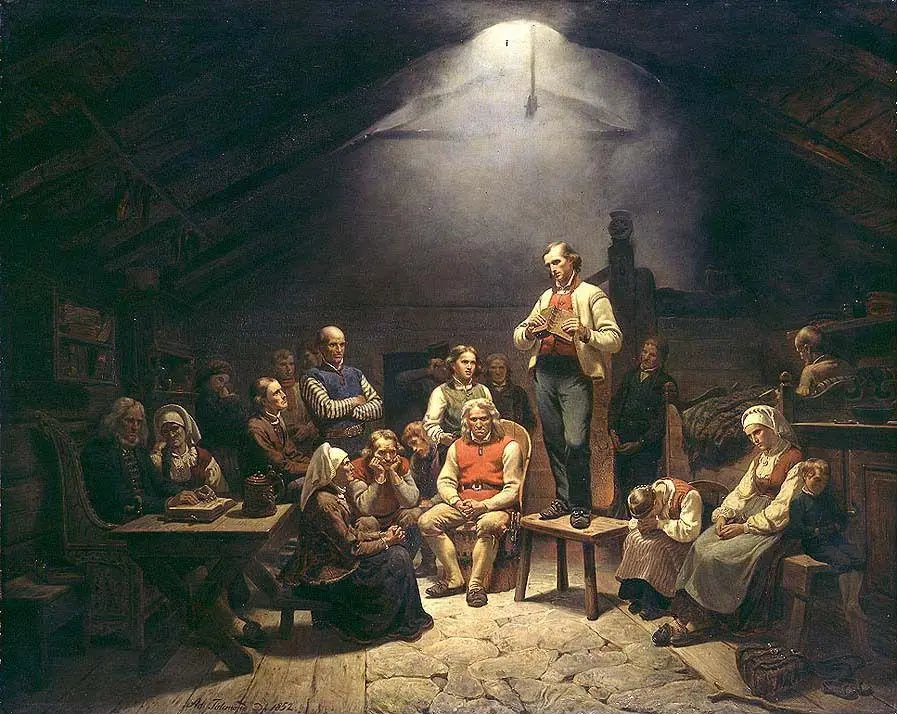

Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771–1824) was a Norwegian lay preacher and reformer who led a religious revival in the early 19th century. He emphasized personal faith, humility, and practical action, inspiring social and economic change. The Haugean movement challenged the Lutheran state church, promoted entrepreneurship, and fostered community empowerment. Despite facing persecution, Hauge’s legacy lives on in Norway’s culture and institutions, including folk high schools. Above: “The Haugians” (1852) by Adolph Tidemand, which depicts Hans Nielsen Hauge preaching illegally as a layman.

The Finnish folk high school movement emerged in the late 19th century during Russian rule, promoting Finnish language, culture and traditions as part of a national awakening. The first Finnish folk high school, founded in 1889 in Kangasala by Sofia Hagman, was a boarding school for young women. It focused on practical skills like handicrafts, alongside subjects such as religion, history and agriculture, empowering women through education and strengthening Finnish national identity.

Inspired by Scandinavian models, particularly the Danish folk high school movement, Finnish institutions emphasized holistic education, including music, arts and physical education. The Kalevala, Finland’s national epic, influenced these schools by reinforcing cultural pride and connection to Finnish heritage.

Amid policies of Russification, folk high schools helped preserve Finnish culture and identity. They also cultivated leaders who contributed to Finland becoming the first country in the world to grant full political rights to women in 1906 and played a crucial role in the country’s independence in 1917 and its cultural revival.

The late 19th century witnessed the rapid proliferation of folk high schools across the Nordic countries, with each region adapting the concept to address its unique cultural and political circumstances. In Denmark, folk high schools continued to focus on national pride and cultural revival, emphasizing Danish history, language, and traditions. Sweden, beginning with Hvilan Folk High School in 1868, placed a greater emphasis on providing rural populations with practical skills and knowledge to navigate a rapidly industrializing society. Norway’s Sagatun Folk High School, founded in 1864, became a symbol of democratic education, fostering civic engagement and individual enlightenment during a time of political and social transformation.

Finland, which joined the movement in 1889 with its first school in Kangasala, used folk high schools as a tool to strengthen national identity and cultural independence amid Russian domination. These institutions played a pivotal role in preserving the Finnish language and promoting the idea of Finnish self-determination. Throughout the Nordic region, folk high schools also emerged as cultural hubs, safeguarding local languages, traditions, and histories against the homogenizing forces of modernization. Gender equality advanced significantly during this period, with schools beginning to admit women on equal terms with men, while evening classes made education accessible to the growing industrial workforce. These regional nuances highlighted the adaptability and cultural specificity of the folk high school model, solidifying its place as a cornerstone of Nordic identity and cohesion.

In recent decades, folk high schools have embraced diversification to remain relevant in a rapidly changing world. The 1970s saw schools addressing the rise of globalization and social movements, integrating themes like environmental activism and participatory democracy into their programs. The advent of digital technology in the 1990s introduced blended and online learning, expanding the reach of folk high schools to new audiences. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these institutions demonstrated remarkable resilience, adapting to virtual platforms while maintaining their core focus on community and dialogue.

Modern folk high schools also actively collaborate with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and governmental bodies to expand their impact. In Denmark, partnerships with environmental NGOs have allowed schools to offer specialized programs in sustainability and climate action. Swedish folk high schools have worked with government agencies to provide vocational training for immigrants, supporting integration and employment opportunities. In Norway, collaboration with UNESCO has promoted global citizenship education, emphasizing peace, cultural exchange, and mutual understanding. These partnerships reflect the ability of folk high schools to address pressing social issues while aligning with international development goals.

Today, folk high schools continue to serve as spaces for lifelong learning, cultural preservation, and global citizenship. They provide a vital blend of tradition and innovation, addressing contemporary challenges while staying true to their foundational values.