Estimated read time: 14 minutes

Ellen Key was born on December 11, 1849, at Sundsholm, a beautiful estate nestled in Gladhammar parish, near the Swedish coastal town of Västervik. Her father, Emil Key, was a progressive politician who encouraged open-mindedness, while her mother, Sophie Posse Key, came from an aristocratic family and brought a love of culture and refinement to Ellen’s upbringing. Growing up in this vibrant intellectual environment, Ellen developed a keen awareness of the social inequalities of her time.

Ellen’s childhood revolved around books, nature, and lively discussions. Her father’s library became her sanctuary, filled with the works of Goethe, Darwin, and Mill, which ignited her intellectual curiosity. Despite these riches, Ellen’s formal education was limited. She was homeschooled by her mother and governesses before attending the progressive Rossander Course in Stockholm. Ellen’s thirst for knowledge drove her to continue learning independently, traveling and immersing herself in Sweden’s reformist circles.

The late 19th century was a time of upheaval and transformation in Europe. Industrialization, urbanization, and movements for workers’ and women’s rights were reshaping society. Ellen Key’s voice emerged as a beacon of hope, calling for compassion and equality in a rapidly changing world.

Ellen’s early writings often addressed social injustices and the need for change. She had a unique ability to weave together bold ideas and heartfelt empathy, which earned her a reputation as both a radical and a deeply human thinker. She believed that art, love, and education held the keys to a more harmonious and fulfilling life for everyone.

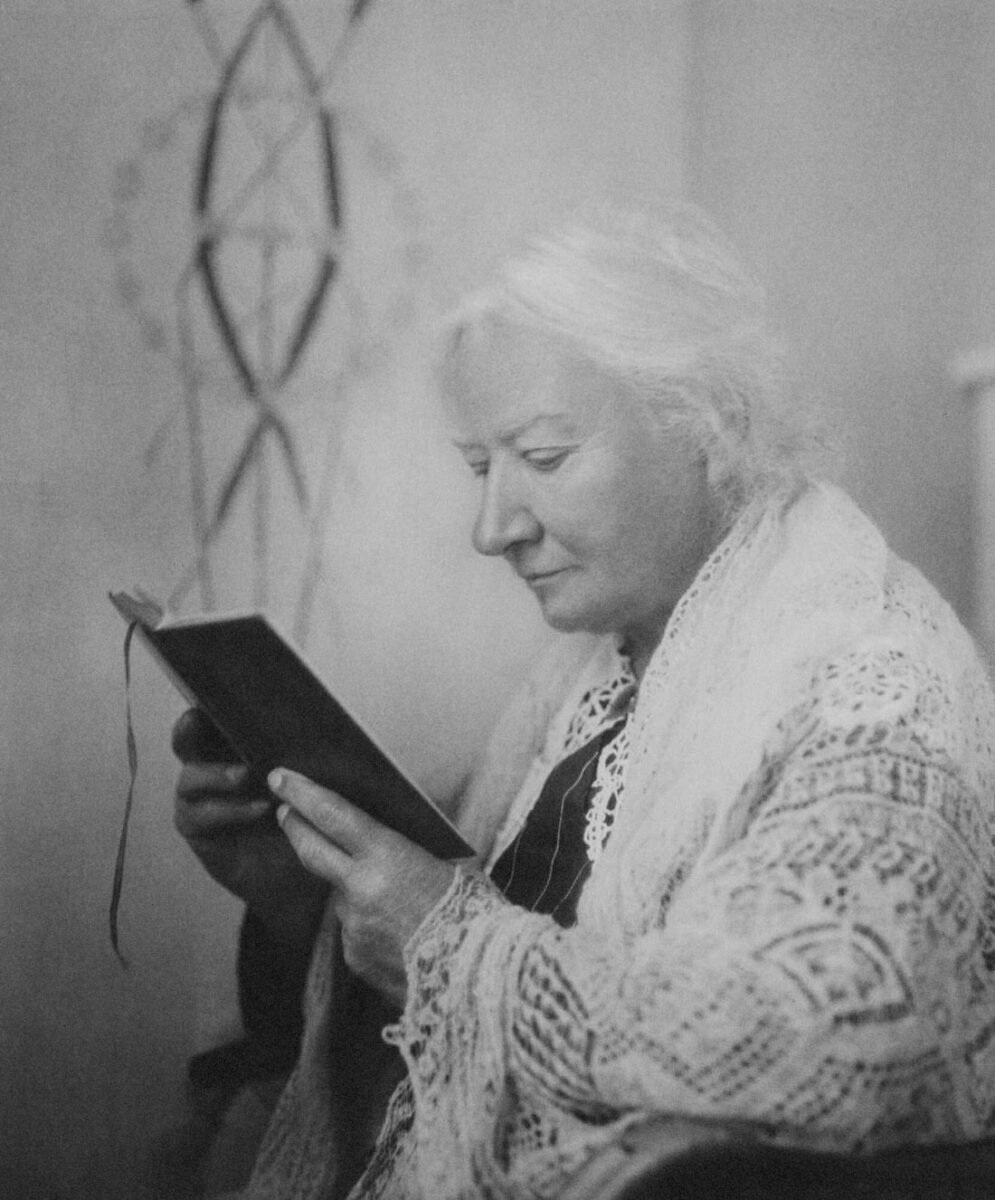

The painting Vännerna (The Friends) depicts Ellen Key, in the light of a kerosene lamp, reading aloud from a book to a group of famous artists and intellectuals of the time, at Bellmansgatan 6 in Södermalm, Stockholm. Painting by Hanna Pauli.

Ellen Key’s advocacy for women was grounded in a deep respect for their potential. She supported access to education and professional opportunities but also placed great emphasis on the value of motherhood. In her book Love and Marriage (1903), Ellen explored the beauty and complexity of relationships, envisioning a future where equality and love went hand in hand.

Some feminists of her time criticized her focus on motherhood, but Ellen saw it as a cornerstone of society and a source of strength. She argued that both women and men needed to be freed from restrictive gender roles to achieve true equality. Her vision celebrated individuality, love, and creativity as forces that could transform not just relationships but entire societies.

Ellen Key’s most famous work, The Century of the Child (1900), is a heartfelt plea for children to be at the center of society’s attention. She dreamed of a world where every child could grow up in an environment of love, creativity, and freedom. To her, education wasn’t just about rote learning; it was about nurturing individuality and sparking joy.

Drawing inspiration from Romanticism, Ellen saw children as inherently good and full of potential. She criticized the rigid, authoritarian education systems of her time for crushing creativity and curiosity. Instead, she championed a more holistic approach that emphasized respect, play, and exploration. She believed teachers and parents should act as gentle guides, helping children blossom into their true selves.

Her ideas resonated across the globe. Figures like Maria Montessori drew inspiration from Ellen’s vision, and her book became a touchstone for progressive education movements. Whether in Germany’s Jugendbewegung, John Dewey’s work in the United States, or educational reforms in Japan, Ellen’s ideas helped shape a world that valued the emotional and intellectual well-being of children.

In 1910, Ellen Key introduced Barnabalk (The Child’s Code), her vision for how society should protect and nurture its children. Building on ideas from her earlier work Barnets århundrade (The Century of the Child), Barnabalk outlined what she believed every child deserved: education that celebrated their individuality, a safe and loving home, and protection from harm. She also called on society to take responsibility for children’s health and well-being, advocating for better housing, healthcare, and support for families.

Key imagined a world where children were treated as individuals with rights, not just as small extensions of their parents. She believed parents had a moral duty to create a caring and supportive environment where children could grow emotionally and intellectually.

Barnabalk had a lasting influence, inspiring child welfare policies in Scandinavia and laying the groundwork for many of the principles found in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). It remains a powerful reminder of how important it is to put children at the heart of a society’s priorities.

The Women’s Suffrage Association (Föreningen för kvinnans politiska rösträtt, FKPR) held a meeting in Huskvarna on June 19-20, 1915, with an excursion to Visingsö. At the Visingsborg castle ruins, Ellen Key stood by the flag and delivered a speech titled “Women’s Will and Women’s Power.”

Ellen Key’s philosophy was deeply humanistic, rooted in a blend of Romanticism, Darwinism, and socialism. She believed in the power of beauty, kindness, and self-expression to uplift individuals and communities. Her writing style reflected this warmth—lyrical, passionate, and full of conviction. Readers felt her sincerity and were moved by her ability to make complex ideas accessible and inspiring.

Ellen Key is born on December 11 at Sundsholm estate in Gladhammar parish, near Västervik, Sweden. Her father, Emil Key, is a liberal politician and founder of the Swedish Agrarian Party, and her mother, Sophie Posse Key, comes from an aristocratic family.

Ellen moves to Stockholm and attends the progressive Rossander Course, a rare educational opportunity for women at the time.

Visits Denmark to study folk high schools, which significantly influence her educational philosophy.

Begins her literary career by publishing essays that gain attention in Sweden’s intellectual circles.

Begins her teaching career at Anna Whitlock’s school for girls in Stockholm.

Expands her teaching career by joining Anton Nyström’s People’s Institute, reflecting her commitment to adult education and social reform.

Co-founds the women’s society Nya Idun, alongside Calla Curman, Hanna Winge, Ellen Fries, and Amelie Wikström, promoting intellectual exchange and women’s rights.

Publishes Tankebilder (Thought Images), a collection of essays reflecting her humanistic and reformist ideas.

Releases her groundbreaking work, Barnets århundrade (The Century of the Child), which argues for child-centered education and reforms in child-rearing practices.

Publishes Kärleken och äktenskapet (Love and Marriage), exploring the connections between love, gender equality, and societal norms.

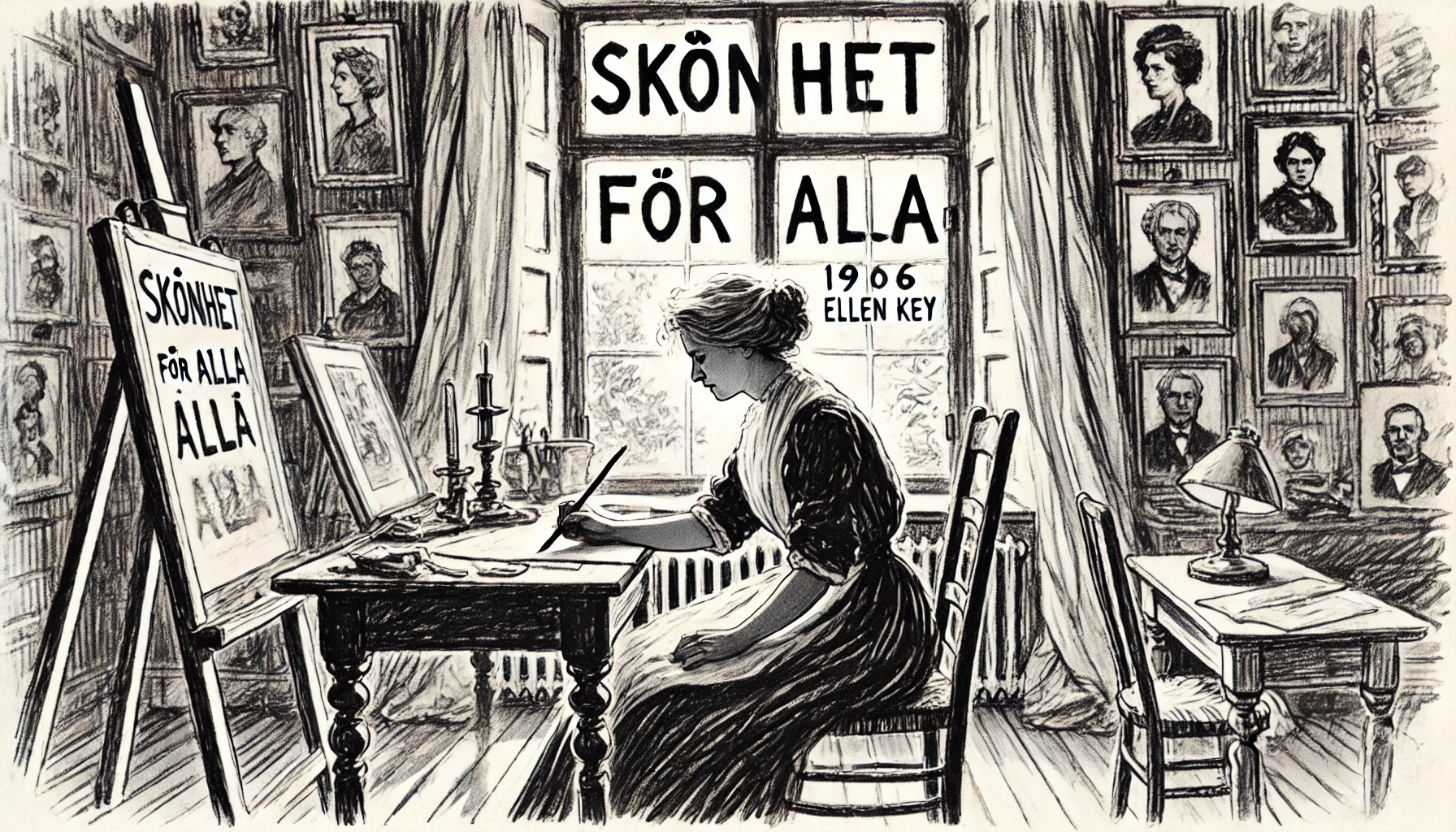

Writes Skönhet för alla (Beauty for All), advocating for the democratization of art and beauty in everyday life.

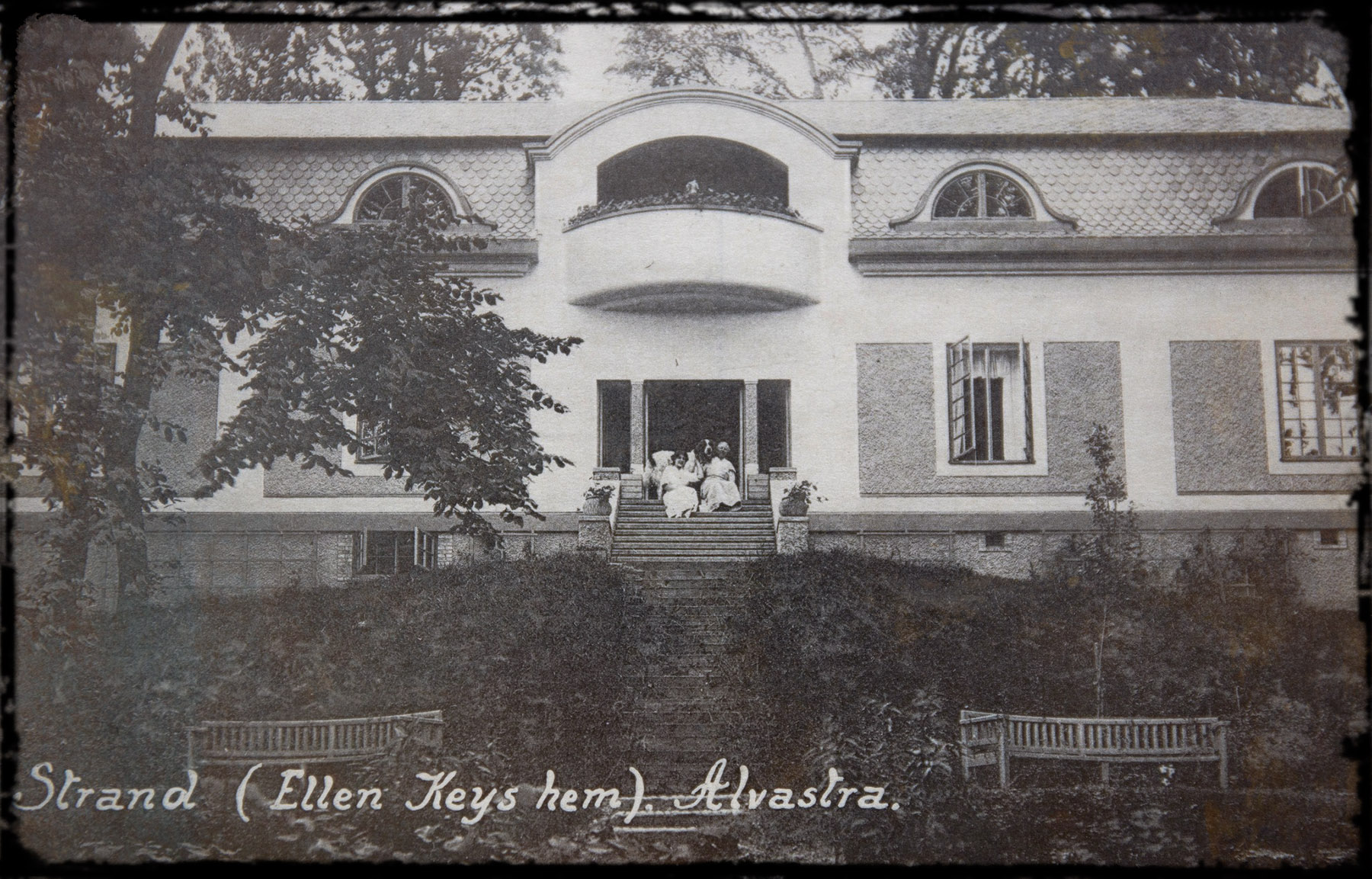

Builds Strand, her home overlooking Lake Vättern, where she spends her later years writing and hosting intellectuals from across Europe.

Publishes Lifslinjer, del 1: Människor (Lifelines, Part 1: People), reflecting on her personal experiences and philosophical views.

Ellen Key passes away on April 25 at Strand, leaving behind a legacy of progressive ideas on education, women's rights, and social reform.

While Ellen Key’s ideas inspired many, they also sparked significant debate and criticism. Her educational ideals, though visionary, were often deemed too idealistic and impractical for widespread implementation. Critics argued that her emphasis on individuality and creativity lacked sufficient structure to meet the needs of public education systems. Additionally, some feminists challenged her romanticized portrayal of motherhood, contending that her focus on women’s roles as caregivers reinforced traditional gender expectations and limited opportunities for broader personal and professional growth.

One of the most controversial aspects of Key’s legacy is her support for eugenics, a view shared by many intellectuals of her time but one that now starkly contrasts with her humanistic and egalitarian principles. While Key believed such measures could improve societal well-being, her advocacy for selective breeding is widely seen today as inconsistent with the inclusivity she championed in other areas. These tensions, alongside critiques of her approaches to education and gender, have sparked ongoing discussions about the complexities of her philosophy and the historical context in which she worked.

What is Eugenics?

Eugenics refers to beliefs and practices aimed at improving the genetic quality of a population by encouraging reproduction among those deemed “fit” and discouraging or preventing it among those considered “unfit.” Emerging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was closely tied to racial biology, a pseudoscience that categorized humans into hierarchical racial groups. These ideas fueled harmful policies such as forced sterilization and discrimination, disproportionately targeting marginalized communities.

Ellen Key’s Views on Eugenics and Racial Biology

Ellen Key supported aspects of eugenics as part of her vision for societal improvement. Influenced by contemporary evolutionary thought, she believed controlled reproduction could prevent societal “degeneration” and enhance human development. Key’s focus was less on racial hierarchies and more on general health, education, and child welfare.

However, Key endorsed institutions like the Swedish Institute for Racial Biology, reflecting the racialized thinking prevalent in her time. While her emphasis was often on broader human progress rather than overt racial superiority, her acceptance of eugenic principles remains a complex and troubling aspect of her legacy.

Ellen Key with her maid Malin Blomberg and St. Bernard dog Wild, at her serene home Strand by Lake Vättern.

In her later years, Ellen Key retreated to Strand, a house she built overlooking the serene waters of Lake Vättern. Surrounded by nature’s beauty, Strand became a haven for Ellen and a gathering place for intellectuals and reformers from across Europe. Here, she wrote, reflected, and continued her mission to create a more compassionate world.

Life at Strand was simple yet rich. Ellen believed that a beautiful and harmonious environment could nurture the soul. She filled her home with light, art, and warmth, embodying the ideals she held so dear. Despite her advancing age, Ellen remained engaged in contemporary debates, hosting lively discussions and sharing her insights with visitors. Strand was more than a home; it was a living expression of her philosophy.

When Ellen Key passed away in 1926 at her beloved Strand, she left behind more than books and ideas. She left a living legacy of hope—a belief in the potential of every individual to create a better world. Ellen’s voice still echoes, reminding us to nurture the best in ourselves and others.

Ellen Key’s legacy is a testament to her courage and compassion. Her ideas about education, women’s rights, and social reform continue to resonate in modern debates. She showed the world that love, beauty, and individuality could be powerful tools for change. Today, educators, feminists, and dreamers draw inspiration from her vision of a more just and humane society.

In the summer of 1925, 17-year-old Astrid Lindgren, long before her fame, visited Ellen Key’s home, Strand, by the tranquil shores of Lake Vättern. Astrid and a friend wandered into the garden and encountered Key’s large St. Bernard dog, Wild, who unexpectedly bit one of the girls. Ellen rushed to help, inviting them inside, where her maid, Malin, kindly treated the wound.

Malin’s nurturing demeanor may have inspired the character of Malin Melkersson in Vi på Saltkråkan. Likewise, the encounter with Wild could have influenced Lindgren’s portrayal of Båtsman, the loyal family dog in the same series. Inside Strand, Astrid noticed an inscription: “Denna dagen ett liv” (“This day, a life”). This phrase left a deep impression on her and later became a recurring theme in her work.

Ellen Key was born into a family that combined liberal political ideals with aristocratic traditions. Her upbringing at Sundsholm estate fostered an early appreciation for intellectual growth and cultural refinement, shaping her progressive outlook on education and equality.

Questions to Reflect On:

Key’s groundbreaking book Barnets århundrade (The Century of the Child) called for child-centered education and a rejection of authoritarian teaching methods. Her ideas highlighted the importance of nurturing individuality and emotional intelligence in children.

Questions to Reflect On:

In Kärleken och äktenskapet (Love and Marriage), Key explored themes of gender equality, love as a moral foundation, and the redefinition of relationships. Her work challenged societal norms, advocating for unions based on mutual respect and affection.

Questions to Reflect On:

Key’s 1906 work Skönhet för alla (Beauty for All) argued that art and beauty should be accessible to everyone, not just the elite. She saw aesthetics as essential to personal fulfillment and societal well-being.

Questions to Reflect On:

In 1910, Key built her home Strand by Lake Vättern, a retreat that embodied her ideals of simplicity, harmony with nature, and intellectual pursuit. Strand became a symbol of her philosophy and a place of inspiration for many.

Questions to Reflect On:

Ellen Key’s contributions to education, gender equality, and cultural appreciation have had a lasting impact. Her ideas influenced social legislation in several countries, and her works continue to inspire educators, feminists, and thinkers worldwide.

Questions to Reflect On:

References