Estimated read time: 16 minutes

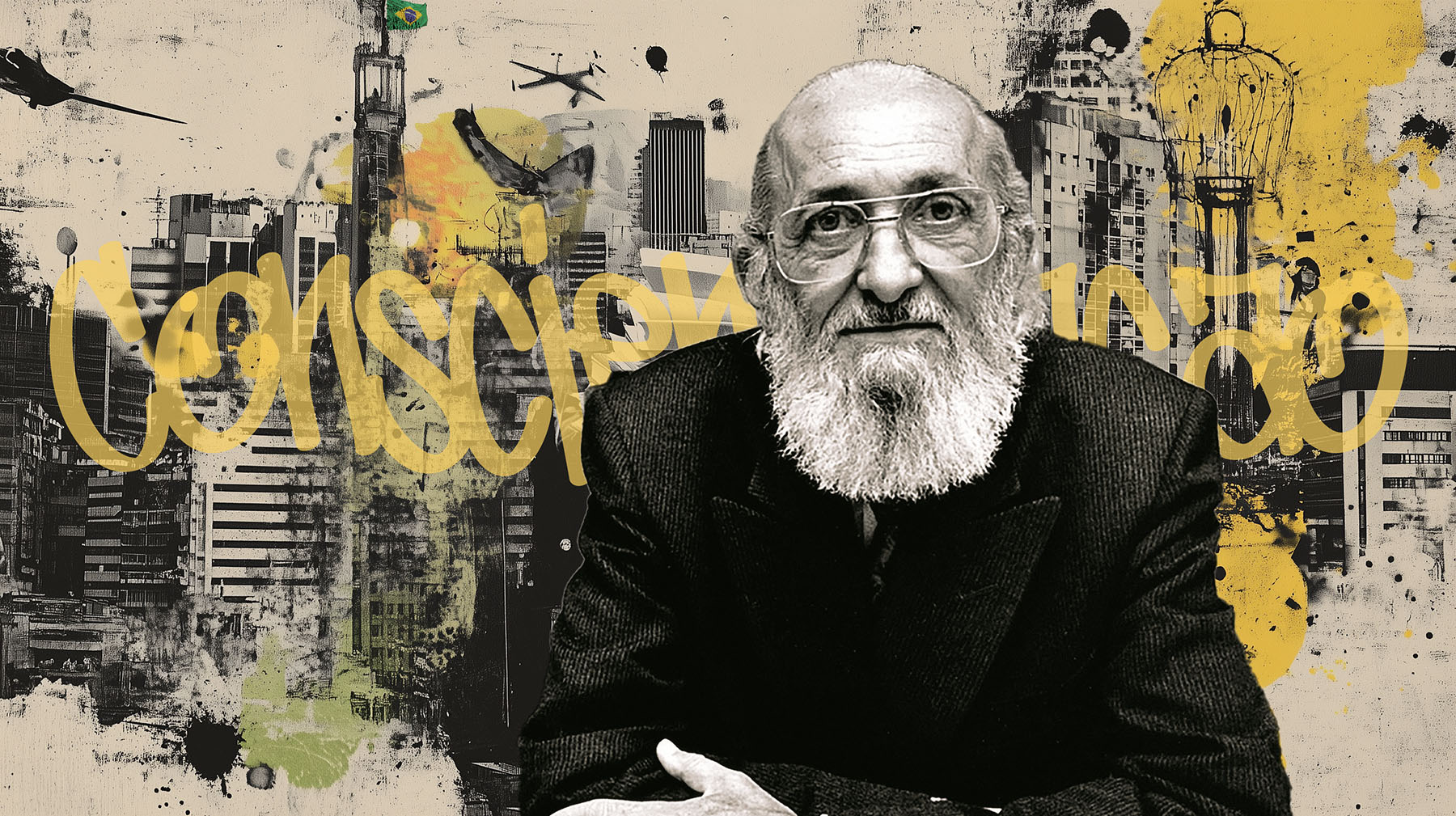

Paulo Freire (1921–1997) was a revolutionary educator whose work reshaped the global understanding of teaching and learning. From his early days in Brazil to his influential book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire’s ideas centered on empowering individuals through education to challenge oppression and transform society. Exiled for his progressive methods, he became a global advocate for justice, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire educators worldwide.

Freire’s educational philosophy is more than a set of theories—it is a deeply humanistic call to use education as a force for liberation. He believed that education is never neutral; it either supports the existing social order or challenges it. For Freire, the purpose of education was to empower individuals to think critically about their world and take action to transform it.

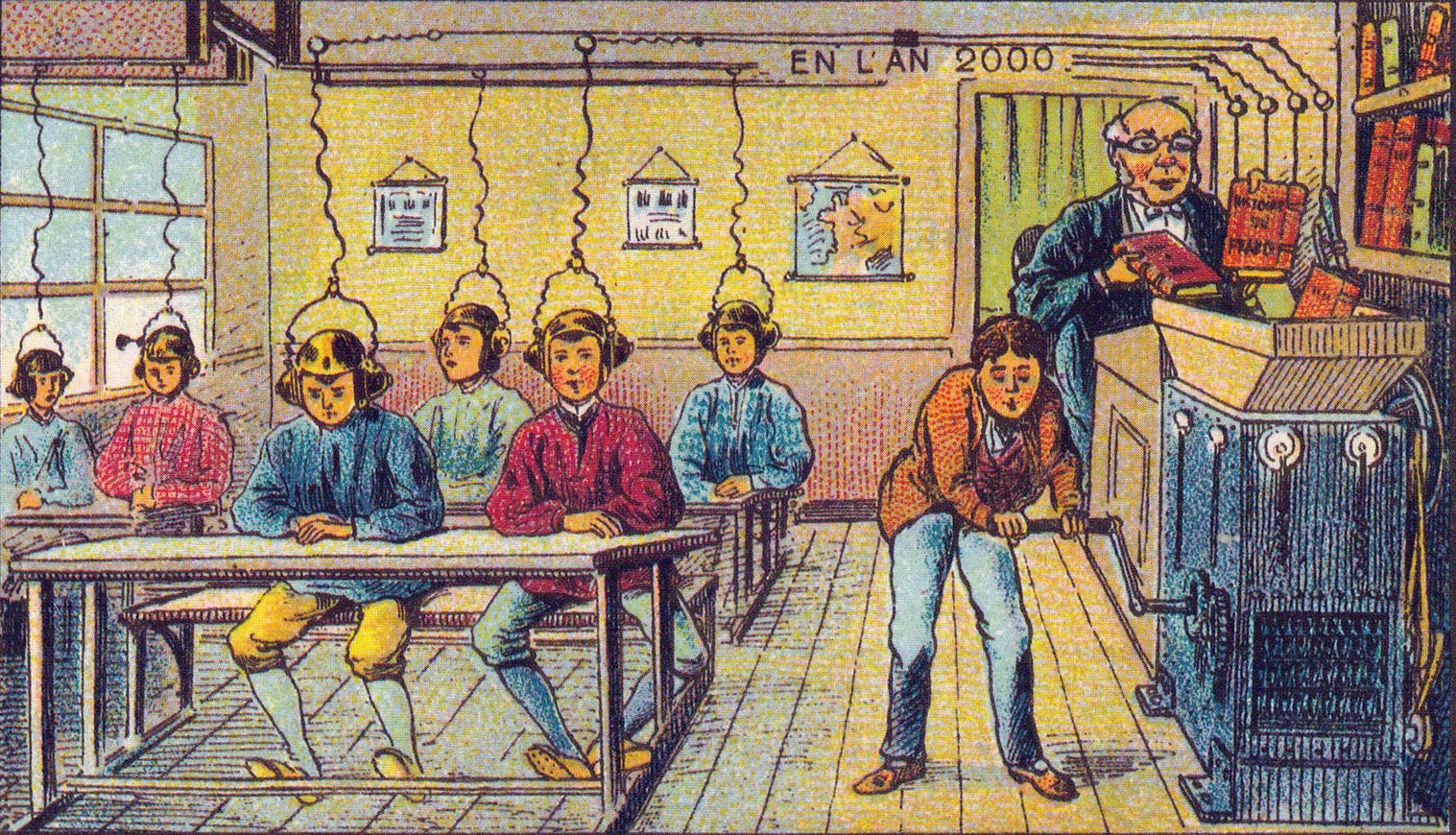

He critiqued what he called the “banking model” of education, where teachers treat students as empty vessels to be filled with knowledge. To Freire, this dehumanizing approach stifles creativity and critical thinking. Instead, he envisioned education as a dialogue—a partnership between teacher and student. By fostering mutual respect and collaboration, the classroom becomes a dynamic space where knowledge is co-created.

Freire’s philosophy emphasizes the connection between learning and lived experience. By rooting education in the cultural, social, and economic realities of students, it becomes a powerful tool for awakening critical consciousness. This “conscientização” enables individuals to see systemic injustices and take meaningful action to change them.

Freire’s vision for education is deeply humanistic, rooted in love, solidarity, and hope. He believed that learning is not just about acquiring information but about transforming society. Through what he called “problem-posing education,” Freire encouraged students to question the world around them, fostering curiosity, empowerment, and a sense of agency.

At its core, Freire’s approach sees students not as passive recipients but as active participants in their own learning. By linking education to real-world challenges, learners are inspired to become agents of change, capable of envisioning and creating a more just and equitable future.

Jean-Marc Côté’s “Future School” (part of the En L’An 2000 series created for the 1900 World Exhibition) envisions a mechanized transfer of knowledge. This contrasts sharply with Paulo Freire’s philosophy, which rejects passive learning in favor of dialogical education that fosters critical thinking and empowerment.

Freire’s landmark book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), remains one of the most influential works in educational theory. Written during his exile in Chile, the book draws on his experiences with marginalized communities and reflects his unwavering belief in education as a tool for empowerment. Freire articulates the dynamic between oppressors and the oppressed, emphasizing that true education invites the oppressed to become active participants in their own liberation. Through dialogue and solidarity, he argued, educators and students could dismantle oppressive structures and create a more equitable society. This transformative vision continues to guide educators and activists worldwide, inspiring them to believe in the power of education to change lives.

First published in Portuguese in 1968 and in English in 1970, Pedagogy of the Oppressed is Paulo Freire’s most influential work and a cornerstone of critical pedagogy. Translated into numerous languages, the book has achieved global acclaim, selling more than one million copies. Widely studied and frequently cited, it is recognized as the third most referenced book in the social sciences, underscoring its profound and enduring impact.

Freire’s exile was both a personal loss and a global opportunity. In Chile, he collaborated on agrarian reform projects, employing his educational methods to empower rural farmers. These initiatives demonstrated how education could serve as a vehicle for social transformation, even in highly stratified societies. Later, as a consultant for the World Council of Churches in Geneva, Switzerland, Freire advised governments and organizations on education reform. His work in post-colonial nations like Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique was especially impactful, as his literacy campaigns became integral to rebuilding national identities. Freire’s ability to adapt his philosophy to diverse cultural and political contexts highlighted his versatility and commitment to justice and human dignity.

Liberation theology is a movement born in the 1960s in the heart of Latin America, where deep poverty and inequality shaped the lives of millions. At its core, it is about seeing faith as a call to action—a way to stand in solidarity with the poor and oppressed. Drawing inspiration from the teachings of Jesus, it calls for justice, dignity, and hope, urging believers to challenge the systems that perpetuate suffering.

Figures like Gustavo Gutiérrez, whose book A Theology of Liberation ignited the movement, and Oscar Romero, a martyred archbishop, became its passionate voices. Liberation theology continues to inspire those committed to transforming society. For Paulo Freire, its message of empowerment and hope was a perfect harmony with his belief in education as a force for liberation.

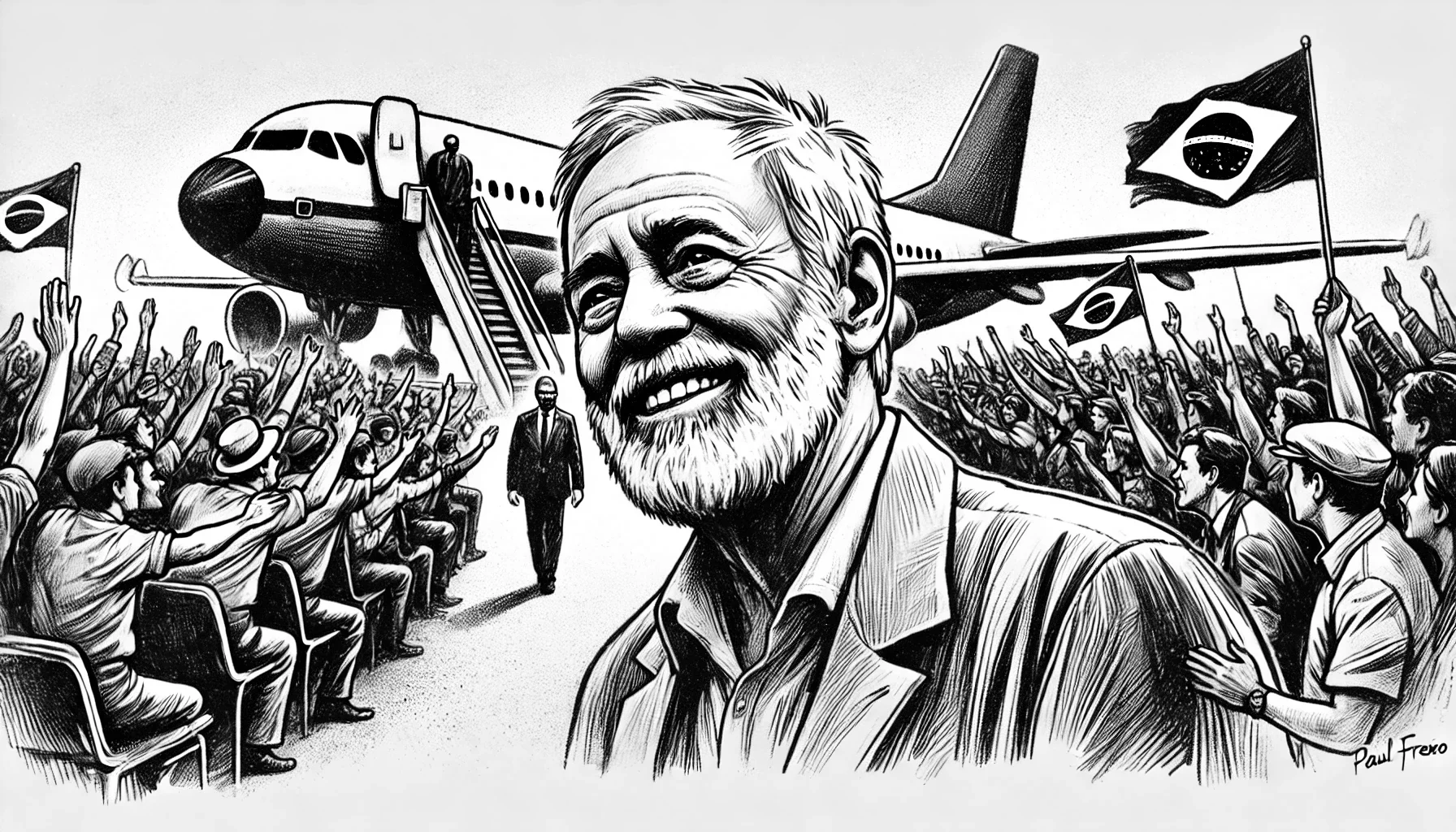

In 1980, Freire returned to Brazil as the country began transitioning toward democracy after years of military rule. Freire joined the Workers’ Party and served as Secretary of Education in São Paulo from 1989 to 1991. During this time, he implemented reforms that brought his philosophy to life. By emphasizing community participation and inclusivity, Freire encouraged teachers and students to co-create curricula reflecting local realities and challenges. This approach not only enhanced literacy but also cultivated civic engagement, empowering communities to play an active role in shaping their future.

Paulo Freire’s emotional return to Brazil in 1980 after 16 years in exile was met with warmth and admiration. Greeted by supporters, students, and intellectuals, his homecoming marked the beginning of a renewed commitment to education and social justice in his homeland.

Freire’s transformative ideas have not been without controversy. Critics argue that his focus on political education can overshadow the importance of vocational training and practical skills, which are crucial for economic advancement. Some scholars also question whether his Marxist-inspired framework is universally applicable, particularly in systems emphasizing standardized curricula or operating in diverse cultural contexts.

Implementing Freire’s dialogical methods within rigid, highly structured educational systems has proven challenging. Critics have raised concerns about whether his emphasis on ideological perspectives risks promoting indoctrination instead of fostering truly independent critical thinking.

Supporters, however, point out that Freire’s pedagogy is inherently adaptable. They highlight examples of teachers integrating his methods with local contexts, blending technical education with critical awareness to equip learners for both societal participation and professional success. Proponents also argue that his focus on dialogue and empowerment encourages not indoctrination but the development of engaged, thoughtful citizens.

Paulo Freire is born on September 19 in Recife, Brazil, to a middle-class family.

Freire's family moves to Jaboatão dos Guararapes due to financial hardships during the Great Depression.

Freire's father passes away on October 31.

Enrolls in the Faculty of Law at the University of Recife but chooses to focus on education.

Marries Elza Maia Costa de Oliveira, an elementary school teacher.

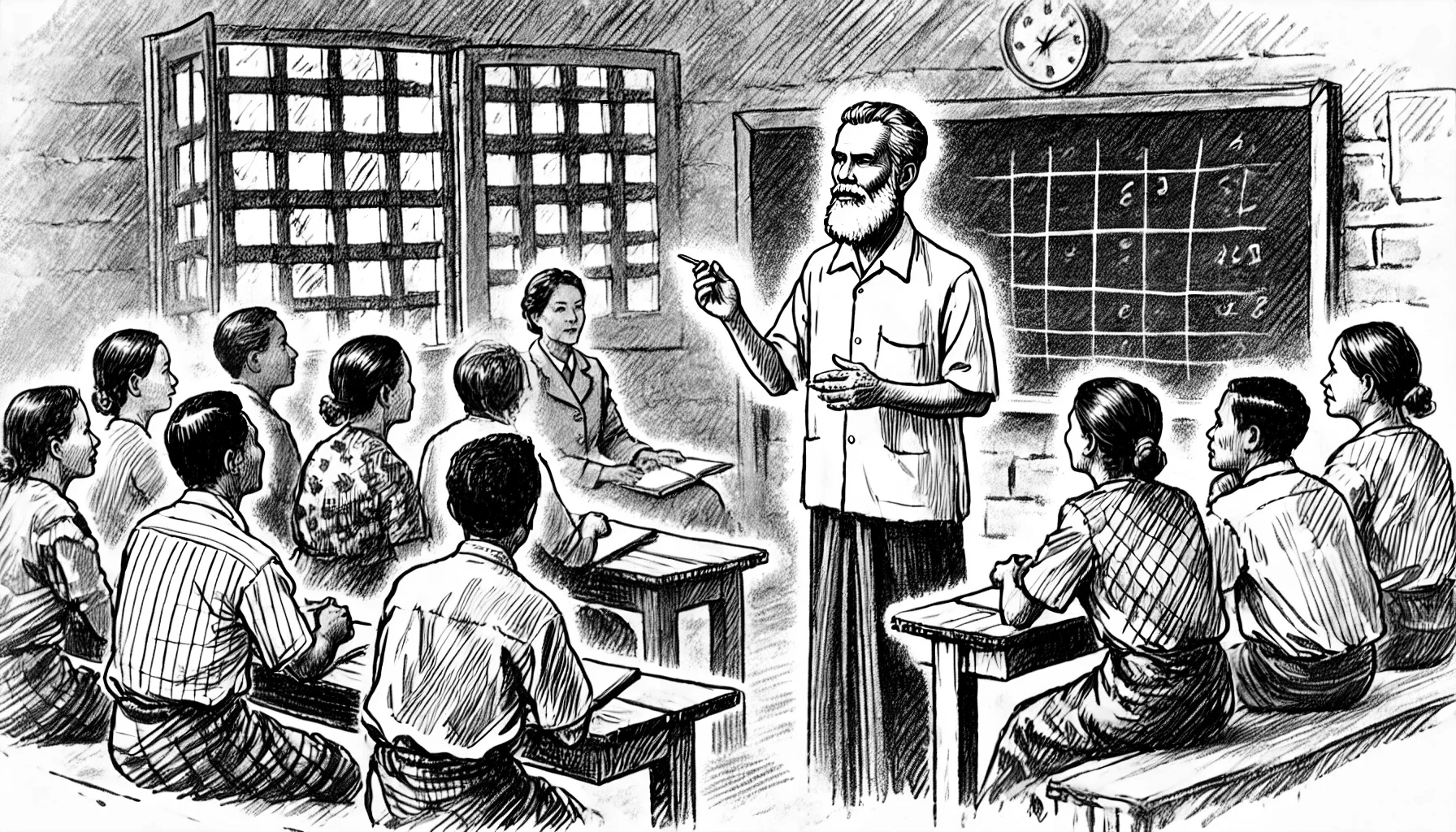

Begins work with adult illiterates in Northeast Brazil, developing his educational methods.

Becomes Director of the Department of Cultural Extension at the University of Recife, initiating literacy programs.

Leads a literacy program in Angicos, Rio Grande do Norte, teaching 300 sugarcane workers to read and write in 45 days.

Following a military coup in Brazil, Freire is imprisoned for 70 days and later goes into exile.

Publishes his first book, Education as the Practice of Freedom, while in exile in Chile.

Completes Pedagogy of the Oppressed in Chile; it is published in Spanish and English in 1970.

Serves as a visiting professor at Harvard University.

Joins the World Council of Churches in Geneva as a special consultant in the Office of Education.

Returns to Brazil after 16 years in exile; becomes involved with the Workers' Party in São Paulo, overseeing its adult literacy project.

His first wife, Elza, passes away.

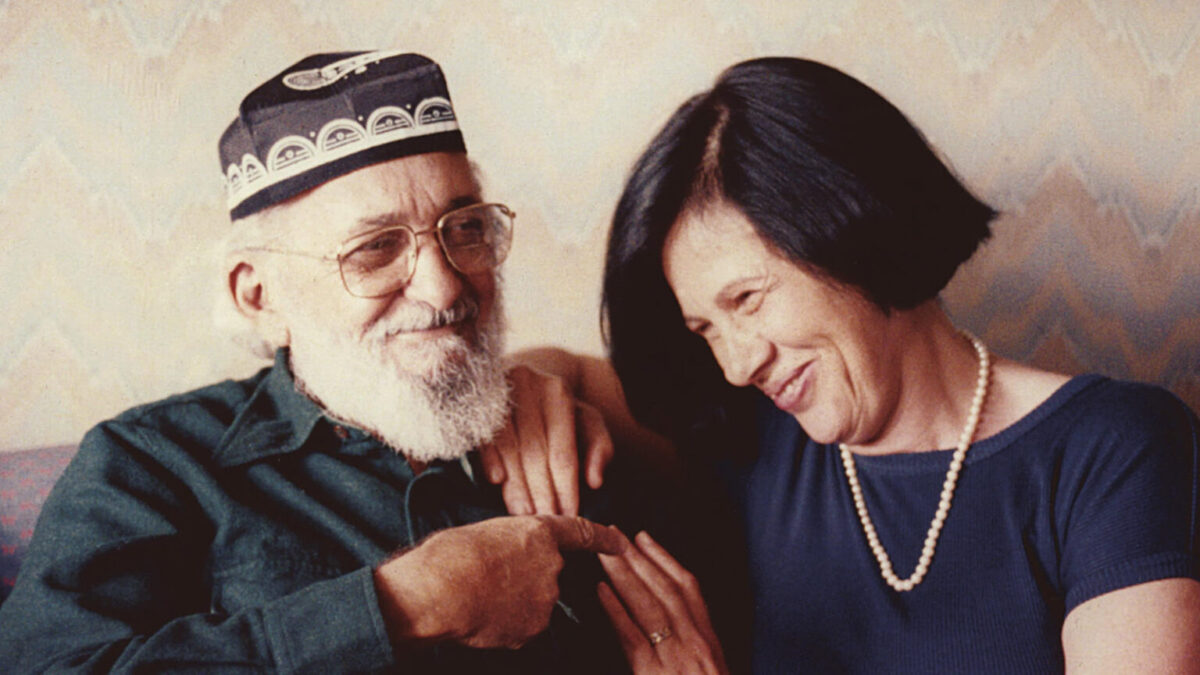

Marries Ana Maria Araújo Freire (Nita).

Appointed Secretary of Education for São Paulo, implementing educational reforms.

The Paulo Freire Institute is established to extend his pedagogical ideas.

Passes away on May 2 in São Paulo, Brazil.

Posthumously declared the Patron of Brazilian Education.

Paulo Freire’s legacy is one of unwavering hope and resilience. His profound belief in humanity’s potential continues to inspire educators, activists, and communities striving for justice and equity. His recognition as Brazil’s patron of education in 2012 underscores his enduring influence, even amid debates over his methods. Freire’s ideas remain relevant as educators address contemporary challenges like inequality in digital access and systemic barriers to education. Institutions like the Paulo Freire Institute carry forward his mission, ensuring that his dream of education as a tool for liberation evolves to meet the needs of future generations.

Freire’s philosophy fundamentally reshaped how we think about teaching and learning. His critiques of traditional education systems and his focus on dialogue invite us to consider the deeper purposes of education.

Questions to Reflect On:

Freire believed that education should be a tool for liberation, empowering marginalized communities to challenge systemic oppression. His ideas connect the classroom to broader struggles for justice.

Questions to Reflect On:

Freire’s exile and international work spread his ideas far beyond Brazil. His influence shaped educational practices and social movements worldwide, making his philosophy a cornerstone of critical pedagogy.

Questions to Reflect On:

Freire’s work continues to inspire educators and activists across the globe. His emphasis on critical consciousness and empowerment remains relevant in addressing today’s educational challenges.

Questions to Reflect On:

Freire’s belief in education as an act of love and hope challenges us to think about our own experiences and roles in education. These questions encourage personal connections to his work.

Questions to Reflect On:

Paulo Freire used this term to describe traditional education systems where teachers treat students as passive recipients of knowledge. In this model, teachers “deposit” information into students, like money into a bank. Freire believed this approach dehumanizes learners, stifling creativity and critical thinking, and called for a more engaging and human-centered way of teaching.

Freire’s alternative to the banking model invites teachers and students to collaborate as co-learners. In problem-posing education, dialogue and questioning take center stage, encouraging students to think critically and connect learning to their real-world experiences. This approach empowers learners to see themselves as active participants in shaping their world.

At the heart of Freire’s philosophy is the idea of conscientização—a journey of becoming aware of social, political, and economic injustices. By understanding their realities more deeply, people can take action to challenge oppression and create meaningful change in their lives and communities.

For Freire, education is more than just learning facts—it’s about reflection and action working together. Praxis is the cycle of thinking critically about the world and then taking steps to transform it. Freire believed this ongoing process of reflection and action is key to personal and social liberation.

Freire saw dialogue as the cornerstone of education. True dialogue is a respectful and open exchange of ideas where both teachers and students learn from each other. This approach builds mutual understanding, fosters critical thinking, and nurtures a sense of shared humanity.

Freire explored the power dynamics between oppressors and the oppressed. He believed the oppressed must reclaim their humanity by challenging the systems that dehumanize them. This struggle isn’t about revenge—it’s about creating a world where everyone can live with dignity and equality.

Freire’s work is rooted in the belief that all people deserve to be treated with dignity. Humanization is the process of affirming someone’s worth and agency, while dehumanization occurs when systems or individuals deny others their humanity. Education, for Freire, was a path toward reclaiming humanization for all.

Deeply influenced by liberation theology, Freire believed education and faith should work hand in hand to address injustice. Liberation theology calls for solidarity with the poor and oppressed, emphasizing action to create a more just and compassionate world—a principle that shaped Freire’s entire philosophy.

Freire encouraged starting education with the “generative themes” of students’ lives—the issues and challenges they face every day. By anchoring learning in real-life struggles, these themes spark meaningful dialogue and empower students to explore solutions together.

Freire used this term to describe how oppression silences the voices of the marginalized. This “culture of silence” discourages critical thinking and reinforces systemic inequality. Freire’s goal was to break this silence, helping people find their voices and their power.

In his literacy programs, Freire used codification—turning real-life situations into images or words—as a starting point for learning. Decodification followed, as learners analyzed these situations critically, sparking new awareness and action. This method made learning deeply relevant and transformative.

Freire believed education should be a path to freedom. Liberatory education goes beyond acquiring knowledge—it’s about fostering critical awareness, encouraging action, and empowering people to challenge systems of oppression. It’s education as a tool for liberation.

For Freire, education is never neutral. It either reinforces the status quo or inspires individuals to question and change it. Political education, in Freire’s view, must align with the fight for justice, equity, and the dignity of all people.

References