Estimated read time: 12 minutes

Born on October 20, 1859, in Burlington, Vermont, John Dewey grew up in a modest family during the industrial revolution. The sweeping changes of his time—urbanization, inequality, and social upheaval—shaped his belief in the power of individuals to create a better world.

After earning his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University, Dewey embarked on a teaching career that would span institutions like the University of Michigan, the University of Chicago, and Columbia University. Along the way, he embraced the pragmatism of thinkers like William James, blending philosophy with a commitment to real-world impact.

Dewey was never satisfied with the rigid, authoritarian classrooms of his time. To him, these methods stifled creativity, curiosity, and the joy of learning. He dreamed of schools that prepared students not just for tests, but for life.

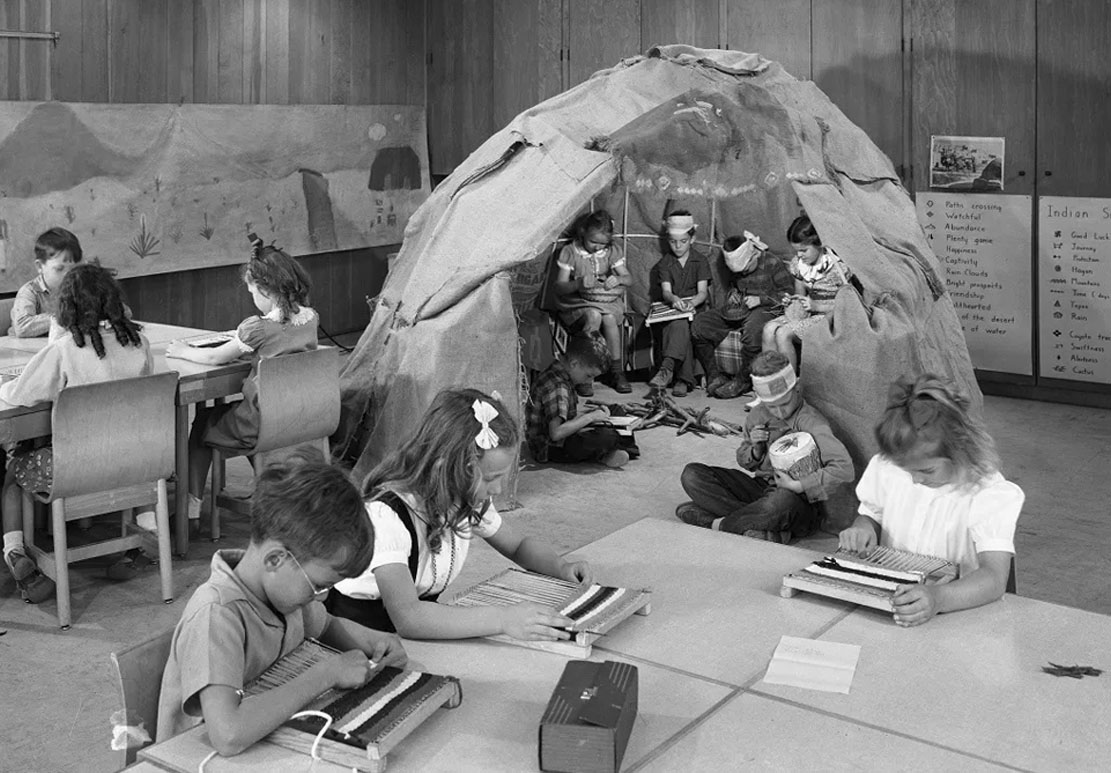

He pioneered the idea of experiential learning—where students engage in hands-on activities that connect classroom lessons to real-world problems. In his landmark book Democracy and Education (1916), Dewey argued that schools should be more than preparation for life; they should be vibrant spaces where students actively practice collaboration, respect, and civic responsibility.

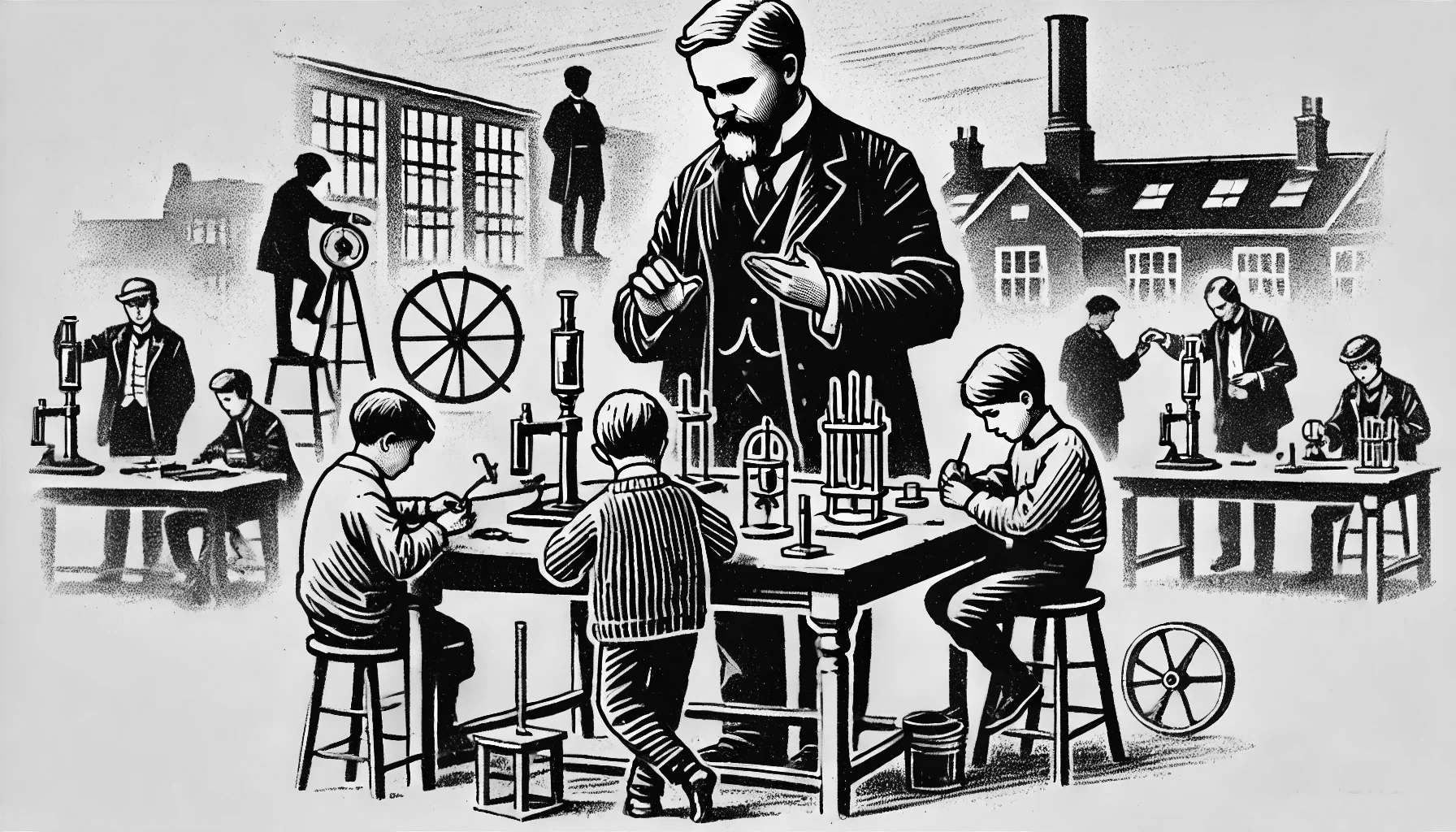

Classes at John Dewey’s Laboratory School. Crow Island Classroom (1940).

In 1896, Dewey turned theory into practice by founding the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago. Here, children explored subjects through projects that combined academic knowledge with everyday skills.

One memorable example involved a cooking project where students learned not only practical skills but also the science of heat, the chemistry of ingredients, and the economics of managing resources. For Dewey, these activities weren’t extras — they were central to learning, making education meaningful and relevant.

He envisioned teachers as mentors and guides, not authoritarian figures. Their role was to nurture curiosity and encourage exploration, creating an environment where students could thrive as independent thinkers.

“Learning by doing” is a cornerstone of John Dewey’s educational philosophy, emphasizing hands-on activities and reflection to make learning meaningful and practical. At his Laboratory School in 1896, students engaged in projects like cooking to learn science and chemistry, gardening to explore biology, and woodworking to apply geometry.

This approach connects academic concepts to real-world experiences, fostering critical thinking and problem-solving. Today, it influences methods like project-based learning, where students create solutions to real-life challenges, and inquiry-based learning, which encourages exploration and discovery. Rooted in Dewey’s belief that education is life itself, “learning by doing” remains a transformative tool for modern classrooms.

Dewey believed that education and democracy were inseparable. For a society to thrive, its citizens needed to think critically, communicate effectively, and work together toward common goals. Schools, he argued, weren’t just places to learn facts—they were where democratic values were forged.

His vision extended beyond individual students. Dewey saw education as a tool for addressing inequality and empowering marginalized communities. He believed schools should reflect the needs of society, fostering justice, equality, and the skills necessary to build stronger communities.

Long before “social-emotional learning” became a buzzword, Dewey championed the importance of addressing students’ emotional and social needs. He believed that learning wasn’t just an intellectual process—it involved the whole person.

By creating environments where students felt safe, respected, and engaged, Dewey anticipated modern approaches to mental health and well-being in education. For him, a school that ignored a child’s emotional world wasn’t fulfilling its true purpose.

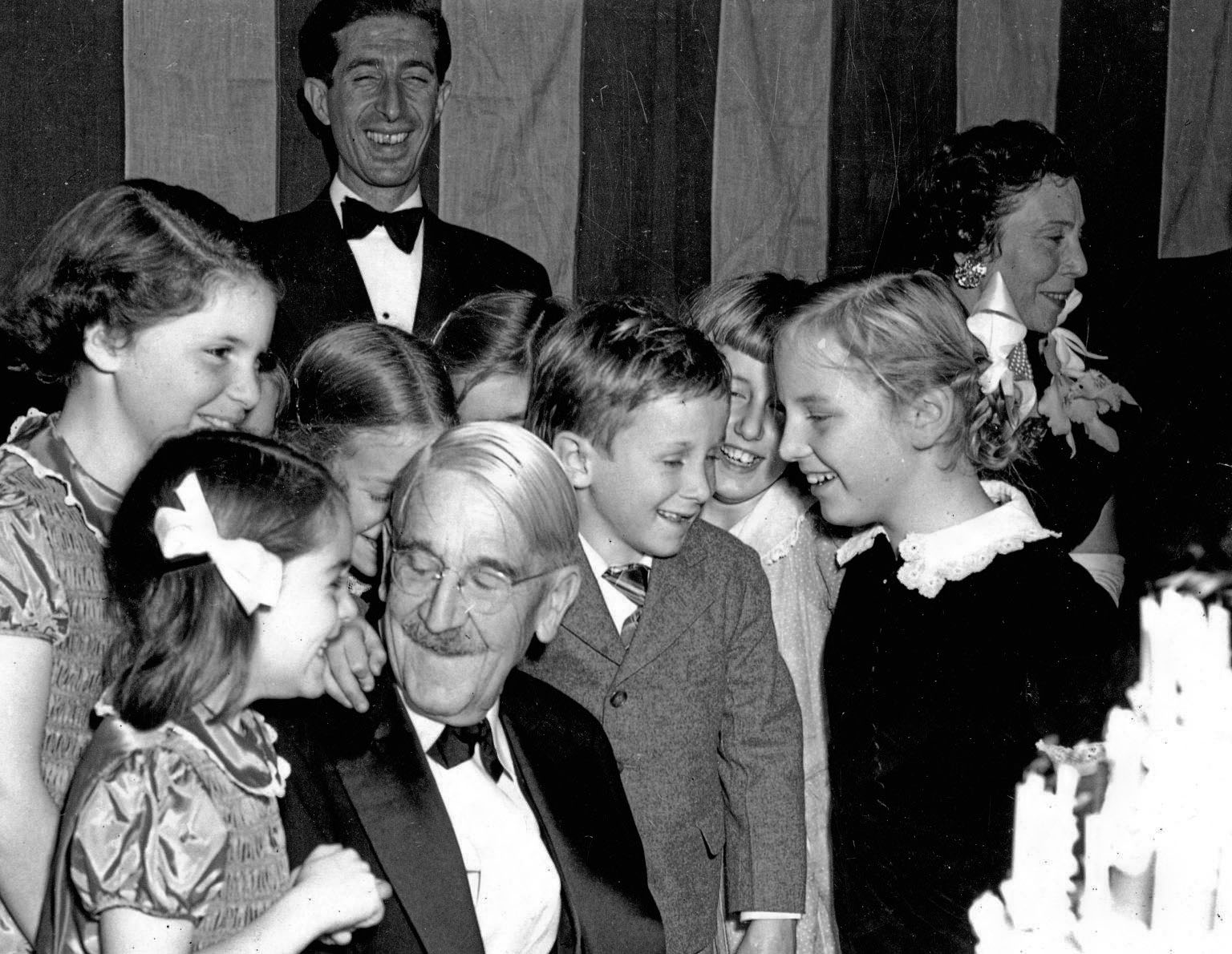

John Dewey celebrates his 90th birthday in 1949, surrounded by children at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City.

John Dewey’s ideas resonated far beyond the United States, shaping education systems in diverse global contexts. In Denmark, his emphasis on community-focused learning paralleled N.F.S. Grundtvig’s folk high school movement, which championed lifelong learning and democratic engagement.

In China, Dewey’s visit in 1919–1921 inspired reformers like Hu Shih and Tao Xingzhi, who modernized the traditional education system by adopting his pragmatic, student-centered methods. Similarly, in Europe, his philosophy influenced nations rebuilding after the World Wars, guiding early childhood education movements such as Reggio Emilia in Italy and fostering democratic values in classrooms.

Dewey’s legacy also reached Latin America, where reformers like Anísio Teixeira in Brazil applied his ideas to promote social progress through education. His influence on global organizations like UNESCO underscores the universality of his belief in education as a foundation for democracy and cooperation.

The Reggio Emilia approach emerged in Reggio Emilia, Italy, after World War II, led by educator Loris Malaguzzi and local parents aiming to create a democratic, child-centered education system. It views children as capable, curious learners and emphasizes hands-on, collaborative learning.

Central to the approach is the idea of the environment as the “third teacher,” with classrooms designed to inspire creativity and interaction. Learning is project-based, driven by children’s interests, with teachers acting as guides rather than authoritative figures. A defining feature is the documentation of children’s work—through photographs, videos, and journals—to reflect on and showcase their learning.

Globally influential, Reggio Emilia aligns with John Dewey’s principles of experiential learning and community integration. It remains a leading model for early education, celebrating individuality, collaboration, and creativity.

John Dewey is born on October 20 in Burlington, Vermont, USA.

Graduates from the University of Vermont with a degree in philosophy.

Earns his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University, focusing on philosophy and psychology.

Teaches philosophy at the University of Michigan, where he begins exploring the connections between education, philosophy, and psychology.

Marries Alice Chipman, an educator and intellectual partner who shares his interest in social reform and progressive education.

Publishes Psychology, his first major work, reflecting his interest in applying psychological principles to education and philosophy.

Joins the University of Chicago, marking a significant shift toward educational experimentation and practical application of his theories.

Founds the Laboratory School at the University of Chicago to implement and test his progressive educational theories.

Publishes Democracy and Education, a landmark work outlining his vision of education as a cornerstone of democratic life.

Travels to China, delivering lectures on democracy and education that inspire reformers like Hu Shih and Tao Xingzhi.

Publishes The Public and Its Problems, exploring the challenges of democratic governance and the role of communication in public life.

Publishes Art as Experience, connecting aesthetics to everyday life and emphasizing creativity as a vital human endeavor.

Releases Experience and Education, a reflection on progressive education and its challenges, clarifying his ideas about experiential learning.

Passes away on June 1 in New York City, leaving behind a vast body of work and a legacy that continues to influence education and philosophy worldwide.

Dewey’s progressive ideas weren’t without critics. Some argued that his methods were too idealistic for large, standardized school systems. Others worried that focusing on hands-on learning might neglect foundational skills like reading and arithmetic.

His belief in the power of education to reshape society was also seen by some as overly optimistic. Could schools alone overcome the deep inequalities and systemic barriers of the time? These questions lingered throughout his career.

Dewey’s influence endures in classrooms worldwide. His commitment to experiential learning, critical thinking, and democratic engagement has shaped the principles of modern education.

In his later years, Dewey reflected on the power of education to connect people to life itself. He once wrote, “Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.” This simple but profound statement remains a guiding light for educators today.

When John Dewey passed away in 1952, he left behind more than theories. He left a living philosophy — one that continues to inspire those who believe in the transformative power of education to build a more just and democratic world.

John Dewey believed that education is not just preparation for life—it is life itself. He emphasized learning through real-world experiences that engage students deeply, rather than relying on rote memorization or passive instruction. Dewey also recognized the importance of emotions, relationships, and the social environment in learning, advocating for a holistic approach long before such ideas were widely acknowledged.

Dewey saw education as essential to a thriving democracy. Schools, in his view, were not just places to acquire knowledge but spaces where individuals learned to think critically, collaborate, and engage with civic life. At the same time, Dewey rejected the authoritarian model of teaching, arguing that education should empower students to discover their passions through guidance and support rather than control.

In his Laboratory School, Dewey demonstrated his belief that education should connect directly to life. He designed hands-on, interdisciplinary projects like cooking and gardening to teach academic subjects in meaningful and practical ways. These projects aimed to make learning relevant to students’ lives while building critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills.

Dewey viewed education as a tool for social reform, believing it could address inequality and empower individuals to create a more just society. He also envisioned schools as “miniature democracies,” where students could practice collaboration, respect, and civic engagement. However, the idea that education alone can solve social issues has always been a point of debate.

John Dewey’s 90th birthday celebration offers a powerful snapshot of his philosophy and influence. The event, held at the prestigious Waldorf Astoria, reflects his significant stature in society, yet the presence of children at the heart of the celebration reinforces his lifelong dedication to child-centered, inclusive education.

While Dewey’s ideas have inspired generations, some critics argue they are overly idealistic. For example, the belief that schools alone can address systemic inequalities or that experiential learning is feasible in standardized systems has been questioned. These challenges remain relevant in modern discussions about education reform.

Dewey’s educational philosophy has had global impact, particularly in contexts where democracy and social cohesion needed rebuilding. His vision resonates with movements like Denmark’s folk high schools, which emphasized community-oriented education to empower citizens. These parallels invite reflection on how Dewey’s ideas might apply in today’s world.

The U.S. Postal Service issued a 30-cent stamp honoring John Dewey on October 21, 1968, as part of the “Prominent Americans” series. The stamp features a portrait of Dewey in red lilac, designed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

It was primarily used for international mail and specific postal rates at the time. The stamp was issued in Burlington, Vermont, Dewey’s birthplace, one day after what would have been his 109th birthday.

References